|

Vito

First Run Features,

2011

Director:

Jeffrey Schwartz

With;

Vito Russo

(archival),

Larry Kramer,

Lily Tomlim,

Michael Schaivi,

Rob Epstein,

Jeffrey Friedman,

Arnie Kantrowitz,

Bruce Vilanch

and many others

Unrated,

93 minutes |

Remembering Vito

by

Michael D. Klemm

Posted online April, 2013

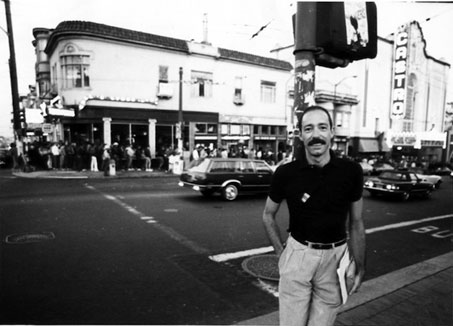

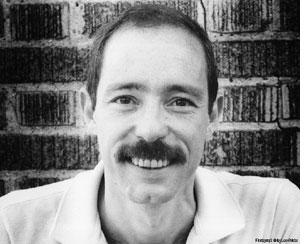

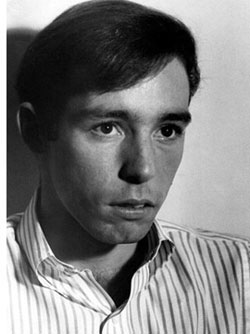

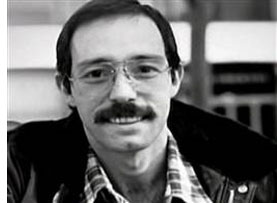

It will come as no surprise to my longtime readers that Vito Russo (1946-1990) is one of my heroes. For starters, Russo wrote the groundbreaking study of gays in the movies, The Celluloid Closet (1981, revised edition 1987) and where would my own Cinemaqueer.com be without the foundation he painstakingly laid? This important critical study, however, is only part of his remarkable legacy. Later, Russo co-founded GLAAD and protested on the front lines with ACT UP. His art and his activism collided in a perfect storm and he remained a force to be reckoned with until his death from AIDS complications in 1990. |

Russo is also the subject of a superb new documentary. Vito aired on HBO in 2012 and is now available on home video. Vito is directed by Jeffrey Schwarz, and based on Celluloid Activist: The Life and Times of Vito Russo, an acclaimed biography published in 2011 by Michael Schaivi. Vito was made by people who loved him and it shows. By using a terrific mix of talking heads and some astounding archival footage, a full portrait of the man, and his times, emerge. By the end of the film, you will feel as if you lost a great friend. Russo is also the subject of a superb new documentary. Vito aired on HBO in 2012 and is now available on home video. Vito is directed by Jeffrey Schwarz, and based on Celluloid Activist: The Life and Times of Vito Russo, an acclaimed biography published in 2011 by Michael Schaivi. Vito was made by people who loved him and it shows. By using a terrific mix of talking heads and some astounding archival footage, a full portrait of the man, and his times, emerge. By the end of the film, you will feel as if you lost a great friend.

|

|

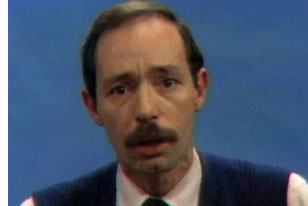

“I made the life I wanted,” Russo tells us in a 1989 interview clip, and he certainly did. Vito focuses on both Russo the film historian and Russo the activist. Both parts of his life were equally important to him and this comes across clearly in the film’s straightforward narrative. Providing much of the film’s core is interview footage with Russo himself. We can see, for ourselves, his warmth, his wit and, of course, his anger. “I made the life I wanted,” Russo tells us in a 1989 interview clip, and he certainly did. Vito focuses on both Russo the film historian and Russo the activist. Both parts of his life were equally important to him and this comes across clearly in the film’s straightforward narrative. Providing much of the film’s core is interview footage with Russo himself. We can see, for ourselves, his warmth, his wit and, of course, his anger.

|

The many talking heads are wisely chosen. Vito is populated by an amazing dramatis personae of the man’s friends and colleagues – a Who’s Who of representatives from our rich history. We will hear from his dear friend Lily Tomlin and from fellow activist Larry Kramer. The many others include filmmakers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman (Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt and the 1995 film version of The Celluloid Closet) and authors Arnie Kantrowitz (Under The Rainbow) and Armistead Maupin (Tales From The City). The many talking heads are wisely chosen. Vito is populated by an amazing dramatis personae of the man’s friends and colleagues – a Who’s Who of representatives from our rich history. We will hear from his dear friend Lily Tomlin and from fellow activist Larry Kramer. The many others include filmmakers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman (Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt and the 1995 film version of The Celluloid Closet) and authors Arnie Kantrowitz (Under The Rainbow) and Armistead Maupin (Tales From The City).

|

Vito is also a family affair. A brother and a cousin relate tales from Russo’s childhood. Vito looked at his cousin’s movie magazines, and she remembers that he always talked about Rock Hudson but not Ava Gardner. Russo knew that he was different at an early age. As a boy, he learned how to use the subways and snuck away to nearby Manhattan to attend matinees. As a teen he found the cruising spots. As a young adult he had sex with men who were ashamed afterwards, and Russo couldn’t understand why they “had” to feel like this. The reason will be clear to the viewer after watching a clip from the notorious 1967 CBS news “expose´” where Mike Wallace tells his television audience that most Americans are “repelled by the very notion of homosexuality.” Vito is also a family affair. A brother and a cousin relate tales from Russo’s childhood. Vito looked at his cousin’s movie magazines, and she remembers that he always talked about Rock Hudson but not Ava Gardner. Russo knew that he was different at an early age. As a boy, he learned how to use the subways and snuck away to nearby Manhattan to attend matinees. As a teen he found the cruising spots. As a young adult he had sex with men who were ashamed afterwards, and Russo couldn’t understand why they “had” to feel like this. The reason will be clear to the viewer after watching a clip from the notorious 1967 CBS news “expose´” where Mike Wallace tells his television audience that most Americans are “repelled by the very notion of homosexuality.”

|

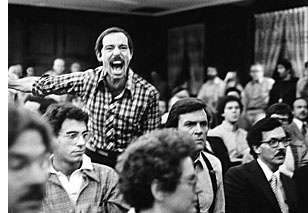

In 1969, Russo sat in a tree and watched the Stonewall riots but his activist side wouldn’t fully erupt until a year later when the police raided another gay bar and arrested 180 men. One of them, an Argentine national named Diego Vinales who feared deportation, jumped from the window of the police station and landed on a spiked fence. That was the turning point for him and, a week later, Russo attended his first meeting of the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). In 1969, Russo sat in a tree and watched the Stonewall riots but his activist side wouldn’t fully erupt until a year later when the police raided another gay bar and arrested 180 men. One of them, an Argentine national named Diego Vinales who feared deportation, jumped from the window of the police station and landed on a spiked fence. That was the turning point for him and, a week later, Russo attended his first meeting of the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA).

|

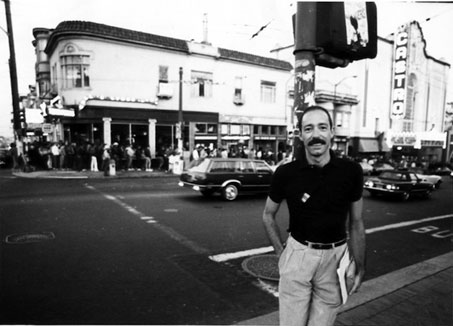

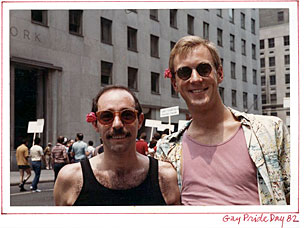

The viewer is treated to a smorgasbord of early gay activism and Gay Pride. The 70s section of the film also celebrates the era's sexual liberation and this is important. Writer / comedian Bruce Vilanch speaks of New York City as a sexual mecca. For Russo, gay liberation and sexual liberation went hand in hand. Filmmaker Jeffrey Friedman laughs and says, “Oh yeah, Vito was a slut. And he was proud of it.” The viewer is treated to a smorgasbord of early gay activism and Gay Pride. The 70s section of the film also celebrates the era's sexual liberation and this is important. Writer / comedian Bruce Vilanch speaks of New York City as a sexual mecca. For Russo, gay liberation and sexual liberation went hand in hand. Filmmaker Jeffrey Friedman laughs and says, “Oh yeah, Vito was a slut. And he was proud of it.”

|

There are too many highlights in this documentary to mention, but one of the best occurs at the 1973 Gay Pride Rally. Factions within the GAA were almost coming to blows and Russo, the Rally’s emcee, is unable to stop the fighting. He saves the day by calling his friend, Bette Midler – a beloved figure from the days when she sang at the Continental Baths – and she hits the stage with a rousing rendition of “You’ve Got To Have Friends” that brings the crowd together. The fact that archival footage of moments like these even exist is reason enough to watch this extraordinary film. There are too many highlights in this documentary to mention, but one of the best occurs at the 1973 Gay Pride Rally. Factions within the GAA were almost coming to blows and Russo, the Rally’s emcee, is unable to stop the fighting. He saves the day by calling his friend, Bette Midler – a beloved figure from the days when she sang at the Continental Baths – and she hits the stage with a rousing rendition of “You’ve Got To Have Friends” that brings the crowd together. The fact that archival footage of moments like these even exist is reason enough to watch this extraordinary film.

|

|

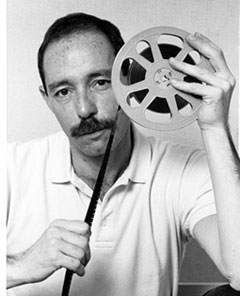

In 1973, Russo began to develop The Celluloid Closet. Its genesis was a series of movie nights at the GAA firehouse. There was catharsis and camaraderie when all-gay audiences discovered that they laughed at the same things, and Russo’s film marathons were a hit. Landing a job in the MOMA’s film department, Russo’s access to their film library enabled him to begin cataloguing the appearances of gays and lesbians in movies as far back as the silent era. The museum’s director, impressed by Russo’s passion, told him that no one has ever researched this neglected subject and that he should write the first book about it. Over the next five years, Russo visited the Library of Congress, and other film institutes all over the globe, and viewed over 400 movies. This research formed the argument that became The Celluloid Closet. |

During this time, he also took a reel of film clips on the road to illustrate his popular lectures - which also were called “The Celluloid Closet.” Vito’s premise was that we have always existed in films but the Hays Code, adopted by Hollywood in 1930, forced homosexuality underground and gay audience members had to look for hidden subtexts. The clips that accompany the film’s narration are well chosen. They range from the 1919 German silent, Different From The Others, to Wings, Rebel Without A Cause, The Boys In The Band, Cruising, The Killing Of Sister George, Rebecca and Rope. We learn how the 1930s sissy stereotypes evolved into screen villains and victims, and then died in the last reel – usually as a suicide (The Children’s Hour, Reflections in a Golden Eye, The Sergeant, amongst others). During this time, he also took a reel of film clips on the road to illustrate his popular lectures - which also were called “The Celluloid Closet.” Vito’s premise was that we have always existed in films but the Hays Code, adopted by Hollywood in 1930, forced homosexuality underground and gay audience members had to look for hidden subtexts. The clips that accompany the film’s narration are well chosen. They range from the 1919 German silent, Different From The Others, to Wings, Rebel Without A Cause, The Boys In The Band, Cruising, The Killing Of Sister George, Rebecca and Rope. We learn how the 1930s sissy stereotypes evolved into screen villains and victims, and then died in the last reel – usually as a suicide (The Children’s Hour, Reflections in a Golden Eye, The Sergeant, amongst others).

|

It’s important that the first actual screen homosexual that Russo saw in a movie theater was in Otto Preminger’s 1962 Advise and Consent. The queer cut his throat at the film’s end and a shaken Russo took that home with him. And so he ended his lectures with a montage of queer screen deaths and the number of them are staggering. If you've never seen it before, your jaw will drop at the clip from 1968’s The Fox as unrepentant lesbian Sandy Dennis is killed when a tree falls on her. Oh, and we can’t forget Sebastian Venable in Suddenly Last Summer. Again, the film clips throughout this terrific middle sequence are very well chosen. The ones that we expect to see are here, like Cary Grant in a frilly nightgown jumping in the air and shouting “I just went gay all of a sudden!” But the filmmakers add many obscure clips as well (there is a rather disturbing cartoon from 1931 featuring a preening dandy who turns into a stark raving lunatic) and that is a testament to the care taken in making this documentary the rich experience that it is. It’s important that the first actual screen homosexual that Russo saw in a movie theater was in Otto Preminger’s 1962 Advise and Consent. The queer cut his throat at the film’s end and a shaken Russo took that home with him. And so he ended his lectures with a montage of queer screen deaths and the number of them are staggering. If you've never seen it before, your jaw will drop at the clip from 1968’s The Fox as unrepentant lesbian Sandy Dennis is killed when a tree falls on her. Oh, and we can’t forget Sebastian Venable in Suddenly Last Summer. Again, the film clips throughout this terrific middle sequence are very well chosen. The ones that we expect to see are here, like Cary Grant in a frilly nightgown jumping in the air and shouting “I just went gay all of a sudden!” But the filmmakers add many obscure clips as well (there is a rather disturbing cartoon from 1931 featuring a preening dandy who turns into a stark raving lunatic) and that is a testament to the care taken in making this documentary the rich experience that it is.

|

Younger generations, weaned on the internet, should especially be impressed with Russo’s achievement. He had to research these films, many of them forgotten, without Google and the internet. And - don’t forget, home video did not exist in the 1970s so it wasn't like he could go out and rent these movies at a neighborhood Blockbuster or stream them on Netflix. Russo himself states, in a late 80s interview clip, that you had to find this stuff - it was not in the library card catalogue. Younger generations, weaned on the internet, should especially be impressed with Russo’s achievement. He had to research these films, many of them forgotten, without Google and the internet. And - don’t forget, home video did not exist in the 1970s so it wasn't like he could go out and rent these movies at a neighborhood Blockbuster or stream them on Netflix. Russo himself states, in a late 80s interview clip, that you had to find this stuff - it was not in the library card catalogue.

|

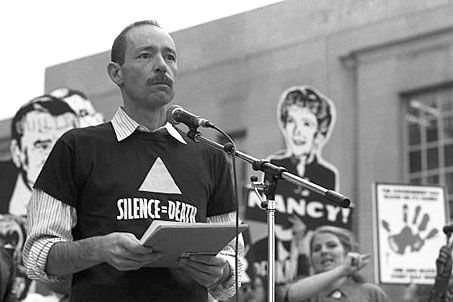

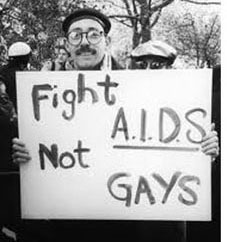

The Celluloid Closet episode is a big part of Vito, but there’s more... much more. The last third, as expected, is heart-wrenching. It is the 1980s. Ronald Reagan is President, the Religious Right has become a dangerous political force, and the AIDS virus is decimating large segments of the gay population. When his longtime partner, Jeffrey Sevcik, succumbed to the disease, Russo’s activism reached new heights. In 1985, outraged by the media's inadequate, inaccurate - and often homophobic - AIDS coverage (especially The New York Post), Russo co-founded GLAAD - The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation to police these news outlets. The Celluloid Closet episode is a big part of Vito, but there’s more... much more. The last third, as expected, is heart-wrenching. It is the 1980s. Ronald Reagan is President, the Religious Right has become a dangerous political force, and the AIDS virus is decimating large segments of the gay population. When his longtime partner, Jeffrey Sevcik, succumbed to the disease, Russo’s activism reached new heights. In 1985, outraged by the media's inadequate, inaccurate - and often homophobic - AIDS coverage (especially The New York Post), Russo co-founded GLAAD - The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation to police these news outlets.

|

B ut even this wasn't enough for our crusader. He would also become, along with founder Larry Kramer, one of ACT UP's most militant protesters. The virus was destroying Russo's health but not his spirit; he still could be counted on to deliver a rousing speech at demonstrations. In 1989, the year before he died, he appeared in Epstein and Friedman’s Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt with the quilt he made for Jeffrey. ut even this wasn't enough for our crusader. He would also become, along with founder Larry Kramer, one of ACT UP's most militant protesters. The virus was destroying Russo's health but not his spirit; he still could be counted on to deliver a rousing speech at demonstrations. In 1989, the year before he died, he appeared in Epstein and Friedman’s Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt with the quilt he made for Jeffrey. |

Although Russo was only in his early 40s, he was recognized as one of the movement's elder statesmen and he made the time to "educate" the younger generation about the history that they were never taught in schools. A few months before he died, Russo - too sick to join the march - was sitting on Larry Kramer's balcony watching the Gay Pride Parade. As the ACT UP contingent passed by, the marchers saw him and began to chant "Vito! Vito! Vito!" This is one of the documentary's most emotional moments and it moved this reviewer to tears. Although Russo was only in his early 40s, he was recognized as one of the movement's elder statesmen and he made the time to "educate" the younger generation about the history that they were never taught in schools. A few months before he died, Russo - too sick to join the march - was sitting on Larry Kramer's balcony watching the Gay Pride Parade. As the ACT UP contingent passed by, the marchers saw him and began to chant "Vito! Vito! Vito!" This is one of the documentary's most emotional moments and it moved this reviewer to tears.

|

Documentaries like this one are important. One of the best things about Vito is that young gay audiences who may have never heard of Vito Russo will now learn about this amazing man while, at the same time, becoming educated about the gay liberation movement through the eyes of a man who lived through a good chunk of it. The notion that a film about him would someday be shown on HBO would probably have been inconceivable to Russo during his lifetime. It’s a sign of how far we have come. Don’t miss this wonderful film. Documentaries like this one are important. One of the best things about Vito is that young gay audiences who may have never heard of Vito Russo will now learn about this amazing man while, at the same time, becoming educated about the gay liberation movement through the eyes of a man who lived through a good chunk of it. The notion that a film about him would someday be shown on HBO would probably have been inconceivable to Russo during his lifetime. It’s a sign of how far we have come. Don’t miss this wonderful film.

|

THE DVD

I think it would have been fun to see something about Russo’s role in the protests during the filming of Cruising but, by the time this film ends, the viewer has certainly enjoyed a filling meal and so I have no complaints. Besides, one of the secrets to making a great documentary is to know when it is getting too long. |

And that’s where DVDs come in. I am happy to report that there are some great extras on this disc if you want more. There are several excerpts from Our Time, which was a gay themed program that Russo wrote, produced and co-hosted in 1983 for WNYC Public Television. Some of this material appears as short snippets in the actual documentary but, thanks to the DVD’s extras, you can watch them at greater length. These include an interview with gay pioneers Harry Hay and Barbara Gittings, and another with Larry Kramer and Virginia Apruzzo about the health crisis. On the lighter side, Vito interviews Lily Tomlin in her Judith Beasely persona as she presents “the Quiche of Peace” to the gay community. My favorite was the interview with Harvey Fierstein, who was doing Torch Song Trilogy on Broadway and had just written the book for the La Cage Aux Folles musical. And that’s where DVDs come in. I am happy to report that there are some great extras on this disc if you want more. There are several excerpts from Our Time, which was a gay themed program that Russo wrote, produced and co-hosted in 1983 for WNYC Public Television. Some of this material appears as short snippets in the actual documentary but, thanks to the DVD’s extras, you can watch them at greater length. These include an interview with gay pioneers Harry Hay and Barbara Gittings, and another with Larry Kramer and Virginia Apruzzo about the health crisis. On the lighter side, Vito interviews Lily Tomlin in her Judith Beasely persona as she presents “the Quiche of Peace” to the gay community. My favorite was the interview with Harvey Fierstein, who was doing Torch Song Trilogy on Broadway and had just written the book for the La Cage Aux Folles musical.

|

There is also a commentary and this one is worth listening to if you want to hear more personal stories about Vito Russo. Rather than the usual “how we made it” commentary, this one is more like a roundtable chat where friends just reminisce. The speakers are director Jeffrey Schwartz; the biography’s author Michael Schiavi; the author of Under The Rainbow and Vito’s friend, Arnie Kantrowitz; and Vito’s brother, Charlie. There is also a commentary and this one is worth listening to if you want to hear more personal stories about Vito Russo. Rather than the usual “how we made it” commentary, this one is more like a roundtable chat where friends just reminisce. The speakers are director Jeffrey Schwartz; the biography’s author Michael Schiavi; the author of Under The Rainbow and Vito’s friend, Arnie Kantrowitz; and Vito’s brother, Charlie.

See also:

The Celluloid Closet

Fabulous: The Story of

Queer Cinema

This Film Is Not Yet

Rated

Lavender

Limelight

More on Jeffrey Schwartz:

Wrangler: Anatomy of an Icon

More on Rob Epstein

and Jeffrey Friedman:

The Celluloid Closet

Howl

Vito Russo appears briefly in:

A Very Natural Thing |

|

THE CELLULOID CLOSET AND ME

If you’re still reading, and don’t mind some self-serving reminiscing, I bought The Celluloid Closet in 1987. It was the revised edition. I was 29, and in the closet. I found the trade paperback at Walden Books. I’d never heard of the book but I stopped dead in my tracks when I saw it. Besides being a closeted queer, I was also a film buff who had taken several film classes in college. This book had my name written all over it. |

My own exposure to queer film was minimal at best at that point. There was La Cage Aux Folles in 1979. There was Making Love in 1982, a film I really needed to see but had the misfortune to watch with an audience that screamed with laughter and made obscene comments. Well, at least Michael Ontkean didn’t kill himself at the end. Oh, there was Kiss Of The Spider Woman in 1985. But the best was this outstanding discovery I made on cable – an independent 1986 film called Parting Glances, which I was pleased to find discussed at length in Russo’s book. |

I devoured this book. The Celluloid Closet made me really think about queer film history for the first time. I didn’t know a lot of the films that he discussed (Pedro Almodovar films did not play in Buffalo in the mid 80s and most video stores weren’t that eclectic), but I did know many of the Hollywood films he wrote about. I’ve always been a big Hitchcock fan but somehow I had never noticed the subtext in Hitch’s 1951 Strangers on a Train until I read about it in Russo’s book. Was I blind? |

I still consider Russo’s book to be the definitive study of queer film history. At least up to 1987. Others have been written in the last decades. They might be more up to date, but the sections on older films are never as entertaining, or as astute, as the insights Russo first shared in 1981. Yes, the book is a product of its times, but that is not a fault. There were no positive images of gays and lesbians in the multi-plexes and so, yes, Russo was often pissed off. He was right when he said that we were starving for images of ourselves on the screen. He was right when he wrote that the great Hollywood dream factory taught straights what to think about gays, and it taught gay people to hate themselves. |

The Celluloid Closet made a big impression on me in 1987. I knew nothing about the author at the time but, a few years later, I would grieve when I learned of Vito Russo’s passing. I also grieved that there could never be a third edition of The Celluloid Closet. |